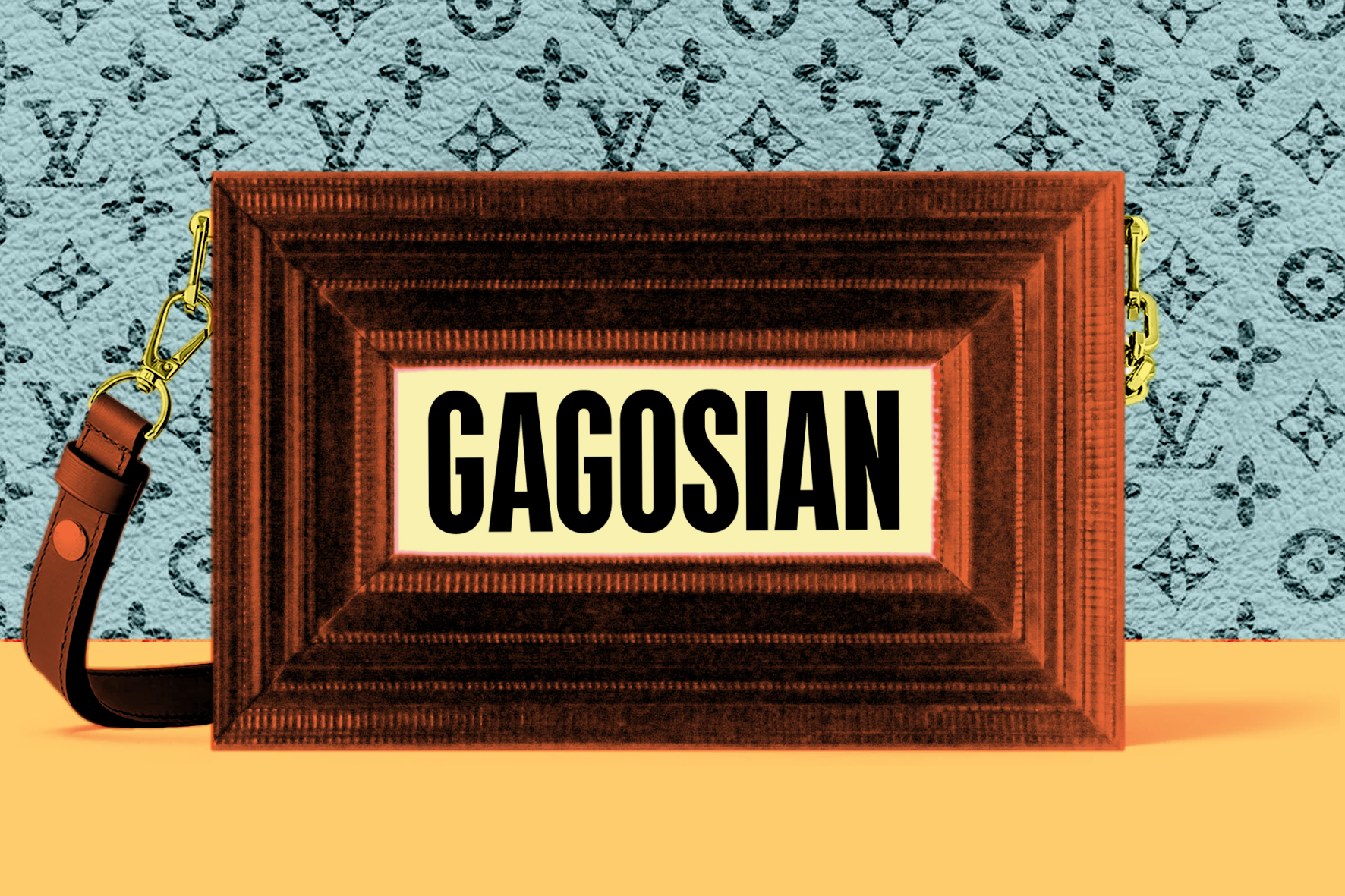

LVMH and Gagosian: why the rumour makes sense, even if it isn’t true

| by Georgina Adam |

Illustration by Katherine Hardy

During the recent European fair splurge, first Frieze in London then the first iteration of Art Basel’s new Paris+ fair, one rumour was flying about everywhere. LVMH (Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy)—the behemoth which, with its rival Kering, dominates the luxury-goods industry—was buying Gagosian gallery. Or it was extending a line of credit worth $1bn to the mega-gallery. Or the rumour was partly correct, in that Larry Gagosian was looking for an exit strategy (he is now 77, with no obvious successor), but it wasn’t with LVMH.

No matter that LVMH and Gagosian vehemently denied everything. The story persists and is being amplified, it must be said, by journalists such as myself and others writing about it.

And yet such an acquisition would make total sense in more ways than one. The most obvious is that LVMH and Gagosian have the same client base: monied collectors of everything from high-end fashion, luxury goods, champagne, watches and jewellery, to... art.

Plus, both are in the business of branding. LVMH’s thundering herd includes Dior, Givenchy, Guerlain, Moët & Chandon and many more. Gagosian is among the most branded art dealers in the business, with the very name evoking a prestigious purchase. Its roster includes some of the juiciest names in contemporary art, from Jadé Fadojutimi to Christopher Wool, with of course a thriving secondary market business, from Bacon to Picasso—who have themselves become top “art” brands.

The act of buying—or rather being allowed to buy—from Gagosian is an accolade in itself: a proof of access, power and wealth. Luxury items are often sold in the same way as art. The “rules” for selling such high-end goods include “making it difficult for clients to buy” (think waiting lists for the hottest artists) and “keep non-enthusiasts out” (think “placing” works of art). These rules come from a book I consulted on about marketing not art, but luxury goods—The Luxury Strategy, by J.M Kapferer and V Bastien.

Gagosian, like LVMH, also does what is called “brand stretching” in commercial speak. You can buy a couture Dior dress for $100,000, or a Dior lipstick for around $30. In the Gagosian shop, an Anna Weyant poster costs $20 and a Jenny Saville t-shirt goes for the same sum. Weyant, famously, is the new 27-year-old sensation who is an “item” with Larry Gagosian and is the gallery’s youngest name; one of her paintings recently sold for $1.6m.

Add to that the international reach of both—Gagosian has 19 spaces around the world—and the growing convergence of art and luxury goods. Today, artists are designing everything from skateboards to yachts: Jeff Koons has produced handbags for Louis Vuitton based on paintings by Turner, Leonardo da Vinci and Fragonard. Bringing Gagosian into the LVMH fold could certainly facilitate more such collaborations.

And finally, a linkup would be an excellent way for LVMH to move its clients on from lipsticks to Lichtenstein, so to speak. At Paris+ par Art Basel, slap bang at the entrance was the Vuitton stand, dominated by a garish Takashi Murakami panda sculpture on a Louis Vuitton trunk... and a wall of handbags.

So even if the rumour isn’t true, maybe it should be: watch this space.